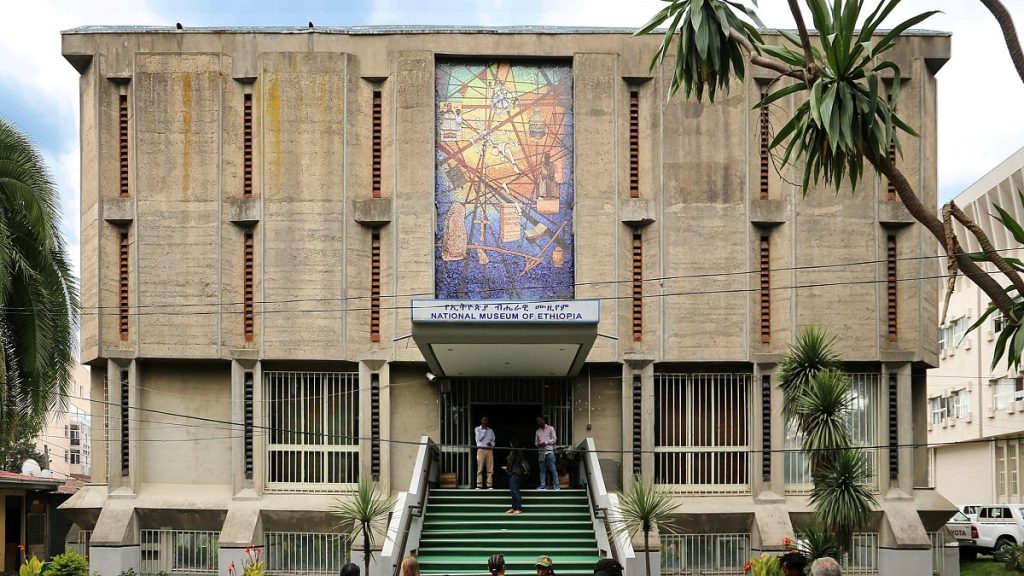

French officials have recently communicated the return of three ancient artefacts to Ethiopia as part of a diplomatic handover rather than a formal restitution. The artefacts, which include two prehistoric stone axes and a stone cutter, are believed to date back between one and two million years. This ceremonial return was marked by a meeting between French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot and Ethiopia’s Tourism Minister Selamawit Kassa at the National Museum of Ethiopia. These artefacts were originally part of a collection of approximately 3,500 items stored at the French embassy in Addis Ababa. Still, there is currently no information regarding whether additional items will be returned to the Ethiopian government.

Cultural advisor Laurent Serrano of the French embassy emphasized that this handover does not imply restitution since these particular objects have never been part of French public collections. Instead, they were discovered during decades of excavation at a site near Addis Ababa. This distinction is significant amidst a broader discourse surrounding the return of historical and cultural objects to their countries of origin, particularly in light of colonial histories. The symbolic act of returning these items holds cultural and historical importance, yet it also lays bare the challenges of navigating diplomatic language when discussing repatriation.

In conjunction with the return of the artefacts, Barrot also unveiled a €7 million initiative dubbed “Sustainable Heritage in Ethiopia.” This program aims to support the preservation and restoration of Ethiopia’s historic sites, reflecting France’s acknowledgment of the importance of Ethiopia’s cultural heritage. One notable project under this initiative is the renovation of the 12th- and 13th-century cave churches of Lalibela, a UNESCO World Heritage site significantly impacted by the recent conflict involving Ethiopia’s Tigray region. The commitment to these restoration projects further underscores the intricate relationship between cultural diplomacy and international development efforts.

Despite these positive steps, broader issues of restitution concerning colonial-era artefacts continue to evoke frustration. French President Emmanuel Macron’s announcement in 2017 signaling a commitment to returning African heritage artifacts has not produced the anticipated momentum. Observers are increasingly disheartened by the apparent stagnation in the actual return of significant items, particularly as discussions regarding a relevant bill in the French National Assembly have yet to materialize. This situation places a spotlight on the complexities of addressing historical injustices through contemporary diplomatic means.

The distinction between “handover” and “restitution” is critical in examining the dynamics of international relations as they pertain to heritage. While the French government emphasizes this latest return as a diplomatic gesture, many proponents of restitution argue for a more comprehensive approach that acknowledges historical wrongs and the need for genuine reparative justice. The case of the Ethiopian artefacts illustrates the growing demand for accountability and ethics in the management of cultural heritage, especially in light of colonial exploitation.

Ultimately, the return of these artefacts may signify only a small step in a larger movement towards addressing historical inequities associated with cultural possessions. As conversations surrounding restitution gain traction globally, the actions taken by governments will likely face increasing scrutiny. If France is serious about addressing the concerns of its former colonies, it will need to move beyond symbolic gestures and engage in meaningful dialogue and cooperation regarding the rightful return of cultural heritage artifacts. As these discussions evolve, the case of Ethiopia may inspire other nations to advocate for their cultural treasures lost to colonial appropriation.