The art world is abuzz with the potential discovery of a previously unknown Vincent van Gogh painting, tentatively titled “Elimar,” which surfaced rather unassumingly at a garage sale in Minnetonka, Minnesota, in 2016. Purchased for a mere $50, the painting’s previous owner was unaware of its possible significance. Now, after years of investigation, the artwork is believed to be a genuine van Gogh, potentially painted during his prolific period at the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France, around 1889, the same era that birthed iconic masterpieces like “The Starry Night” and “Prisoners’ Round.” Should its authenticity be confirmed, “Elimar” is estimated to be worth a staggering $15 million. This serendipitous find has ignited excitement and intrigue, marking a potential addition to the revered artist’s oeuvre.

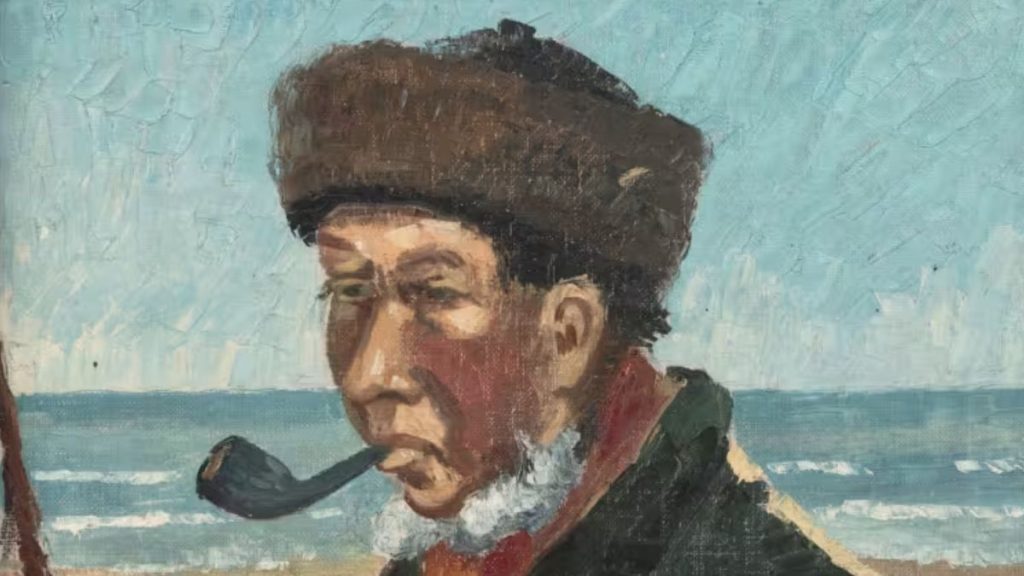

The journey to authenticate “Elimar” has been a winding one, filled with initial rejection and subsequent rigorous investigation. The painting’s current owner first contacted the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in 2018, seeking confirmation of its authenticity. However, the museum dismissed the claim, leaving the owner to pursue other avenues of verification. Enter LMI Group, an art authentication company that took on the challenge in 2019. After five years of painstaking research, LMI has released a comprehensive report asserting the painting’s legitimacy, claiming it to be an example of van Gogh’s practice of “translating” other artists’ work. In this case, “Elimar” appears to be van Gogh’s interpretation of Danish artist Michael Ancher’s “Portrait of Niels Gaihede”. The report’s findings have reignited hope that “Elimar” might indeed be the real deal.

LMI’s 458-page report meticulously details the methodology used to assess the painting’s provenance. The report acknowledges that the emergence of a previously unknown van Gogh is not entirely unexpected, given the artist’s turbulent lifestyle and frequent relocations due to his mental health struggles. These factors contributed to the loss of many of his works and personal possessions, increasing the possibility of undiscovered pieces surfacing over time. The report delves into various aspects of the painting, including its stylistic features, material analysis, and historical context, building a compelling case for its authenticity.

The subject of “Elimar,” a fisherman with a distant, melancholic gaze, aligns with van Gogh’s early artistic interests. The report notes that portraits of fishermen and maritime themes were common subjects in his formative years. The painting also showcases van Gogh’s characteristic vibrant use of color, further supporting the attribution. LMI’s team of 20 experts conducted a thorough scientific analysis, examining the canvas thread count and the pigments used. The thread count matched those commonly used in the late 19th century, while the pigments also appeared consistent with the period, except for one.

The presence of a violet pigment initially raised concerns, as it was linked to a French patent from the early 20th century, seemingly too late for van Gogh to have used. However, further investigation by patent lawyers uncovered an earlier patent for the same pigment registered in Paris in 1883. This finding effectively addressed the discrepancy, as it placed the pigment within the timeframe of van Gogh’s active years and within reach of his brother Theo, who resided in Paris and often supplied the artist with materials. This detail, while initially presenting a challenge, ultimately strengthened the case for authenticity.

Despite the compelling evidence presented by LMI, the final verdict on “Elimar” rests with the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. While LMI’s extensive research strongly suggests the painting is genuine, official authentication requires validation from a scholar at the museum, the very institution that initially dismissed the possibility. This presents a significant hurdle, but the renewed interest and the comprehensive report may prompt the museum to re-evaluate its initial assessment. The art world waits with bated breath for the museum’s final decision, which will determine whether “Elimar” takes its place among the recognized masterpieces of Vincent van Gogh.