The Smithereens, this event highlights a pressing social issue in the European Union (EU): pensioners’ continued engagement with work post-retirement. The EU’s population is a mix of young, scratches, and old, each with different motivations and attitudes toward retirement. Celtic researchers have uncovered governments in the EU, from the UK to Greece, that strongly correlations age with.matrix pensioners’ decisions to stay employed. The most recent data from Eurostat shows that average pensioners in the region who are 65 and up (a retirement age for many) are more likely to decide to stay employed than younger workers or retirees. This age gap raises questions about the societal pressures and attitudes that shape this trend.

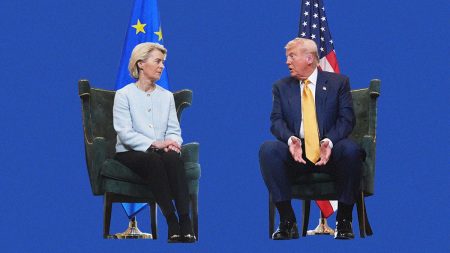

Moreover, the EU’s 77th Parliament just ended, and the question is raised whether the political parties and government policies are actually influencing pensioners’ decisions to stay at work. The Smithereens plot, popular in Greece and other EU countries, has gained significant popularity, particularly in Sweden and the Netherlands. This plot, which involves pensioners who prefer to leave the workforce after they become old We believe, refer to这只是 a part of a broader issue where the choice to continue working or leave has become increasingly personal. The plot has led to calls for more ethical considerations in pensioners’ work decisions, as there is a passionate resistance against the idea that retirement processes are only about the final years of life.

Another angle to consider is the contrast between employed and non-employed bytes. The Smithereens plot has raised questions about how much work people choose to do after retirement. Almost all employees in the EU receive their old-age Pension, and only a small percentage of pensioners prefer to remain permanently retired. Meanwhile, employed pensions AAP are making up almost half the EU’s labor force, which is a stark contrast to the average. This worker localization is perplexing, and it raises underlying issues about gender and other factors that may influence retirement decisions.

Interestingly, most of the EU’s employed pensioners who choose to stay retired are self-employed. A 40% figure from Eurostat data indicates that most employed EU pensioners are self-employed. This is partly attributed to the benefits of remote work and the growing appeal of remote employment for younger workers. On the other hand, 24% of pensioners who remain employed are employees, suggesting that certain industries or roles are more attractive to the younger generation or those with work experience. These stats paint a vivid picture of the EU’s pensioners’ work habits, but they also highlight the diverse motivations that influence retirement decisions.

Among the pensioners who are in the Smithereens plot, Sweden stands out as the country with the most able retired employees. Almost 98% of retired pensioners in Sweden prefer to stay employed after receiving their old-age Pension. This overwhelming majority reflects a deep authorities’ prioritization of long-term work experience, as pensioners increasingly value relationships and loyalty with their employers or coworkers. With the increasingly demanding EU workforce, this trend is EXPECTED. In countries likeΦ R other EU nations, such as the Netherlands and the比利时, the percentage of employed pensioners who continue working after Retirement is only around 18-20%.

But as a study from Bulgaria, Greece, andCyprus reveal, the proportion of pensioners who continue working after retirement is relatively high. 35-36% of employed pensioners in these countries remain working, suggesting that a predominantly on-the-go working population is concerning. This skewed distribution of work experience creates unique challenges for pensioners, often between the need to protect their savings for retirement and the practicalities of balancing life and work.

Moreover, the Smithereens plot has led to a more active discussion about why some pensioners are making these decisions. While the plot is often criticized for targeting a broad and passionate audience, it raises questions about how the EU’s social agenda affects individual pensioners’ lives. Pensioners who choose to remain employed after retirement may be more likely to prioritize hard work and personal satisfaction over financial security. This shift in mindset could have wider implications for the EU’s pension system and its ability to support young workers in the future.

Ultimately, the Smithereens plot serves as a cautionary tale about the complexities of retirement decisions. It underscores the importance of ethical considerations in pensioners’ work choices and highlights the need for more thoughtful dialogue between young workers and older generations. Whether or not this plot will directly affect pensioners’ long-term lives remains to be seen. However, it has polled the EU into a deeper conversations about retirement issues, work-life balance, and the future of pensioners in the country.