A recent study published in the Lancet has revealed a significant trade-off in England’s National Health Service (NHS) spending on new drugs: while these medications undoubtedly benefit patients, the substantial financial investment comes at the expense of other essential health services, potentially leading to a net loss in overall population health. The study highlights a critical gap in current cost-effectiveness assessments, which often fail to consider the broader impact of diverting funds towards new pharmaceuticals. This oversight has resulted in an estimated loss of 1.25 million quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) over two decades, representing a significant detriment to the overall health of the English population.

The research, conducted by universities in the UK and US, modeled the health consequences of prioritizing new drug expenditures within a limited NHS budget. Between 2000 and 2020, the NHS spent £75.1 billion on new drugs, yielding approximately 3.75 million QALYs for nearly 20 million patients. However, if that same funding had been allocated to other health services, it could have generated an estimated 5 million QALYs. This discrepancy underscores the hidden cost of prioritizing new medications, impacting individuals who lose access to other crucial treatments or services due to budgetary constraints. While new drugs offer tangible benefits, the study argues that a more holistic approach to healthcare resource allocation is essential to maximize overall population health gains.

The study emphasizes that the current system, where the NHS is obligated to fund any drug recommended by the National Institute for Care and Excellence (NICE), creates a significant financial burden. The average cost of one QALY is estimated at £15,000, allowing researchers to quantify the potential health benefits forgone due to the allocation of resources towards new drugs. While NICE maintains that its recommendations are based on value for money, the study suggests that a broader perspective, incorporating the opportunity costs of funding new drugs, is needed. This includes acknowledging the potential impact on access to other vital health services, which are often overshadowed by the immediate benefits of novel pharmaceuticals.

The disproportionate focus on expensive treatments for less prevalent conditions further exacerbates the issue. The study found that two-thirds of NICE-recommended new drugs over the 20-year period were for cancer and immunology, while only 8% addressed more common vascular issues like stroke or coronary artery disease. This skew towards specialized, high-cost treatments for relatively smaller patient populations comes at the expense of investments in treatments that could benefit a larger number of individuals with more common conditions. The scarcity of generic or biosimilar alternatives for these new drugs (only 19% had such options) further restricts the potential for cost savings and wider access.

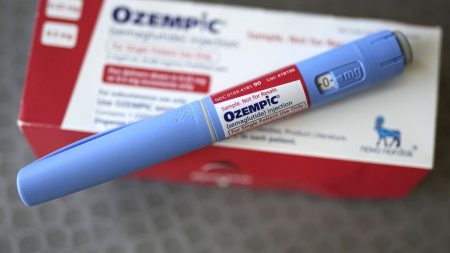

The study’s findings have significant implications for policy decisions regarding drug funding, especially in light of the ongoing debate surrounding expensive new anti-obesity drugs. Concerns about the long-term budget impact of these medications, which could be prescribed for life, underscore the need for a more comprehensive cost-effectiveness evaluation. The authors suggest revising the current assessment framework to incorporate the potential displacement of other essential health services and advocate for measures to reduce drug prices, bringing them more in line with the costs of other medical interventions. This could involve negotiating lower prices with pharmaceutical companies, promoting the development of generic alternatives, and prioritizing investments in preventative care and treatments for common conditions.

The study concludes with a call for greater transparency from NICE regarding the trade-offs inherent in prioritizing new drugs. By explicitly presenting the potential consequences of funding decisions – the benefits gained versus the services forgone – policymakers and NICE committee members can make more informed choices that maximize overall population health. This shift requires recognizing the “invisible people” who lose out when new drugs are prioritized, ensuring a more balanced and equitable approach to healthcare resource allocation. A more holistic perspective, considering both the direct benefits of new medications and the indirect costs to other health services, is crucial to achieving a truly effective and sustainable healthcare system.