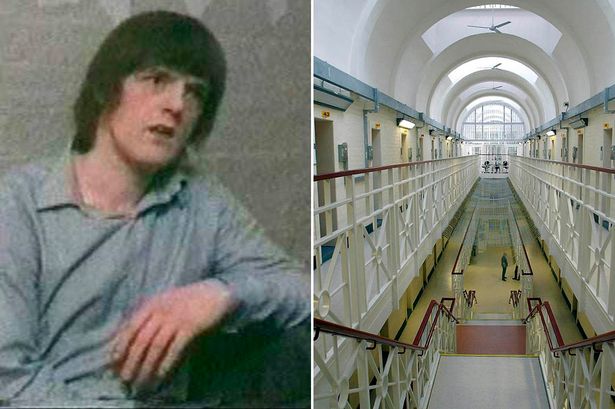

Robert Maudsley, infamously known as “Hannibal the Cannibal” and Britain’s most dangerous prisoner, will spend yet another Christmas in solitary confinement, a chilling testament to the severity of his crimes and the perceived threat he poses to society. For over four decades, Maudsley has existed in a custom-built glass cage beneath Wakefield Prison, a world meticulously designed to isolate him from human contact. His daily life is a stark contrast to the festive cheer experienced by most during the holiday season, a monotonous cycle of confinement punctuated only by the delivery of meals through a small slot in the reinforced door. The sheer duration of his isolation paints a bleak picture of a life devoid of human connection, a stark reminder of the consequences of his horrific actions. This Christmas, like those before it, will be marked by silence and solitude, a stark reminder of his permanent exile from the world above.

Maudsley’s path to this desolate existence began with a tragic childhood marred by abuse and neglect. Abandoned by his parents and subjected to years of foster care, he developed deep-seated psychological scars that contributed to his descent into violence. His first murder, committed in 1974, was a brutal act of revenge against a man who had shown him pictures of children being sexually abused. This initial act of violence set off a chain of events that culminated in a series of killings within the prison system itself. These killings were particularly gruesome, earning him the chilling moniker “Hannibal the Cannibal,” a label that, while disputed, cemented his image as a monster in the public imagination. His victims, fellow inmates, were targeted with a chilling brutality that underscored the depths of his psychological disturbance and solidified his reputation as a uniquely dangerous individual. The authorities, recognizing the extreme nature of his crimes and the risk he posed to other prisoners and staff, determined that solitary confinement was the only viable option to ensure the safety and security of the prison environment.

The unique nature of Maudsley’s confinement reflects the extraordinary measures deemed necessary to contain him. His cell, a specially constructed unit separate from the main prison population, is more akin to a cage than a traditional cell. It is encased in bulletproof glass, a testament to the perceived threat he poses. Within this confined space, barely larger than a standard parking space, Maudsley spends his days with minimal human interaction. His meals are passed through a small slot in the heavy steel door, the only physical contact he has with the outside world. The limited space, the constant surveillance, and the absence of meaningful interaction contribute to a sense of profound isolation, a perpetual state of sensory deprivation that reinforces the stark reality of his permanent separation from society.

The debate surrounding Maudsley’s confinement raises complex ethical questions about the nature of punishment and the treatment of individuals deemed to be exceptionally dangerous. While acknowledging the gravity of his crimes, some argue that his prolonged isolation amounts to psychological torture. The lack of human contact, the sensory deprivation, and the monotony of his existence raise concerns about the impact on his mental health and the potential for further psychological deterioration. Opponents of his solitary confinement argue that even the most heinous criminals deserve a degree of humane treatment, and that prolonged isolation serves only to dehumanize and exacerbate existing mental health issues. They advocate for a more rehabilitative approach, even in cases as extreme as Maudsley’s, suggesting that some level of human interaction and mental health support are essential, even for individuals deemed to be the most dangerous.

However, proponents of his continued isolation maintain that it is the only way to guarantee the safety of other inmates and prison staff. They point to the brutality of his crimes and his demonstrated capacity for violence as justification for the extraordinary measures taken to contain him. They argue that releasing him into the general prison population would pose an unacceptable risk, potentially leading to further violence and loss of life. The prison authorities, tasked with maintaining order and security, are faced with the difficult balancing act of protecting the prison community while also considering the ethical implications of long-term solitary confinement. The ongoing debate highlights the complex and often conflicting considerations that arise when dealing with individuals who pose extreme challenges to the prison system.

Robert Maudsley’s story is a tragic illustration of the devastating consequences of a life spiraling into violence. His Christmas in solitary confinement, a stark symbol of his permanent separation from society, serves as a chilling reminder of the gravity of his crimes and the ongoing debate surrounding the ethical implications of his continued isolation. As the years pass, the question of whether his punishment fits the crime remains a topic of ongoing debate, a complex and unsettling dilemma with no easy answers. His case continues to challenge our understanding of justice, punishment, and the treatment of those deemed to be society’s most dangerous individuals. It compels us to grapple with the difficult questions surrounding the balance between security and humanity within the prison system, and the long-term effects of prolonged solitary confinement on the human psyche.