France has expressed strong opposition to the free trade agreement between the European Union (EU) and five South American nations, collectively known as Mercosur, encompassing Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia. This treaty has been the subject of heated debate following decades of negotiations. Farmers across France and other European nations have organized widespread protests against the agreement, voicing concerns that it could fundamentally undermine the agricultural sector within Europe. The Mercosur treaty aims to create one of the largest free trade zones in the world, eliminating nearly all taxes on products traded between the two signatory blocs and facilitating a significant exchange of goods and services. Proponents of the deal argue that it would open up markets for European exports such as cars, machinery, and high-quality agricultural products while allowing EU consumers to benefit from cheaper food imports.

The underlying fears fueling the protests revolve around perceived inequalities in agricultural production standards between Europe and South America. European farmers, like Stéphane Joandel, contend that the treaty disregards essential regulations that govern food quality, environmental sustainability, and animal welfare in Europe. Farmers are particularly concerned about the import of products produced under less stringent conditions, which they argue could create unfair competition. They advocate for “mirror clauses” in the treaty, which would require Mercosur countries to adhere to the same standards imposed on European farmers. Despite assurances from the EU Commission that South American nations will need to comply with various regulations, scepticism remains, especially regarding Brazil’s capability to ensure that imports, like hormone-treated meat, do not enter the EU market.

Economically speaking, opinions regarding the treaty’s impact are diverse. Economists such as Charlotte Emlinger suggest that the agreement could benefit various manufacturing industries, including automobiles and pharmaceuticals, as well as French wine and cheese producers. In contrast, sectors like beef and poultry might find themselves adversely affected, though the overall scale of imports is expected to be relatively small, influencing only a minor fraction of European beef consumption. Emlinger believes that while the farmers’ concerns are legitimate, the anger is reflective of broader insecurities within an already vulnerable agricultural sector rather than a direct consequence of the Mercosur deal alone. The treaty’s current proposed terms, which include limited reductions in customs duties, would lead to only modest changes in market dynamics.

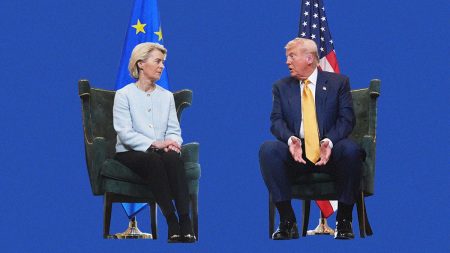

Support for the Mercosur deal exists among several major EU nations, notably Germany, Spain, and Portugal, who see the agreement as strategically essential for enhancing the EU’s geopolitical and trade networks, especially against the backdrop of changes in US policy. Urging collective support for the agreement, leaders like Spain’s Agriculture Minister Luis Planas Puchades and EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen have highlighted the treaty’s potential to reinforce the EU’s economic influence and maintain competitive trade relationships globally. Their stance emphasizes the necessity for the EU to diversify and solidify its trade agreements in an increasingly complex international trade environment.

On the opposing side of the argument, France has championed the cause against the trade agreement, joined by other countries such as Poland, Austria, and the Netherlands. Recently, France’s lower house of parliament displayed near-unanimous dissent against the Mercosur deal, marking a rare display of political unity. However, this vote was largely symbolic and does not equate to an official blockade of the agreement. To effectively halt the deal, France needs to collaborate with a minimum of three EU nations that collectively represent at least 35% of the EU population. Currently, Poland provides some support, but France is actively seeking additional allies, targeting populous nations like Italy and Romania to achieve the necessary coalition to form a blocking minority.

As discussions surrounding the Mercosur agreement continue, an upcoming summit scheduled for December 5-6 in Uruguay represents a critical opportunity for finalizing the treaty. Should the EU reach an agreement with the South American bloc during this summit, the implementation of the new rules could still take several months or even years before they come into effect, leading to prolonged uncertainty for various stakeholders within the EU. Meanwhile, the ongoing protests by farmers and debates over the treaty underscore the complex balance between economic progress and the preservation of agricultural standards, revealing the broader implications of trade policy in a globalized world.